South American Déjà Vu

Venezuela, Gaza, and when the rules stop speaking

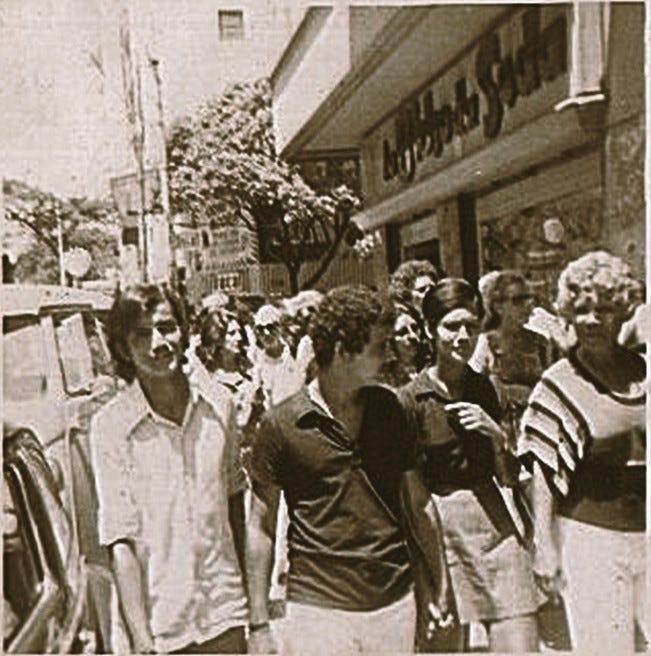

The reaction was immediate and physical.

As the headlines turned again toward Venezuela at the start of 2026 – toward threats, diplomatic pressure, the escalation of military force, and renewed claims over who governs and who controls oil – the body responded before analysis had time to assemble itself. A tightening. The familiar sense that something had crossed a line it would not bother to name.

In South America, force rarely announces itself plainly. It arrives calibrated to sound procedural. In press conferences. In documents. In measures described as temporary, provisional, unavoidable. The vocabulary shifts. The outcome does not.

What mattered was not the choreography of events but the signal beneath them. Sovereignty, once again, had become contingent. Authority relocated. Decisions reframed as management rather than imposition.

This is why Gaza matters far beyond its borders.

Scholars, jurists, and activists have repeatedly situated Gaza within the history of genocide – alongside Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Armenian experience of Nagorno-Karabakh – precisely to establish the gravity of what is unfolding and the legal obligations already in place.

What distinguishes Gaza is what has followed. Extensive documentation exists. Provisional measures have been ordered by the International Court of Justice. Global mobilisation has been sustained. And still, restraint has not materialised. The legal language is present. The institutional machinery is in motion. Its capacity to interrupt power is not.

This reveals something precise about the current order: the applicability of international law depends less on violation than on alignment. Once demonstrated, this condition does not remain confined to one theatre. Rules do not disappear. They remain visible, cited, debated, while steadily losing their force.

Latin America has encountered this configuration before.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm described the region as one repeatedly subjected to external correction when attempts were made to alter property relations, development paths, or political alignment. Instability, in this account, was not a cause but an effect.

In the nineteenth century, Paraguay pursued an unusually autonomous model of development, limiting foreign capital and prioritising domestic industry. The war that followed did more than defeat a government; it dismantled an alternative trajectory.

The twentieth century refined the mechanism. Guatemala in 1954. Chile in 1973. Brazil in 1964. Later, the disciplining effects of debt, austerity, and structural adjustment. More recently, sanctions regimes that hollow out economies while preserving the language of legality. Across forms and eras, the pattern persisted: autonomy incurred cost.

Venezuela occupies this same terrain. Public debate has focused intensely on the character of its government – its legitimacy, its failures, its internal contradictions. Meanwhile, a parallel process has unfolded with far less scrutiny.

External actors assert the authority to recognise leadership. State assets are frozen or transferred. Oil is reframed as a matter of international stewardship rather than national control. Economic pressure is justified as governance.

The present moment sharpens these dynamics.

Across Latin America and much of the Global South, coordination has re-emerged as a governing strategy rather than a rhetorical aspiration. Shared positions on wealth taxation, development finance, industrial policy, and South–South cooperation are beginning to surface in multilateral forums long structured around fragmentation.

Figures such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva serve as indicators: memory returning to institutions. Democracy summits convened outside Western capitals. G20 discussions that treat inequality as structural rather than residual. Limits articulated openly – on accumulation, extraction, impunity.

These are administrative gestures, not revolutionary ones. And administration, when it begins to travel, unsettles established hierarchies.

This convergence helps explain the current landscape: the rise of far-right political forces alongside persistent foreign military presence and intensified economic pressure.

Authoritarianism is identified selectively. Governments aligned with dominant economic interests are framed as stabilising. Governments that pursue redistribution or coordination are framed as risks.

Pressure accumulates through familiar instruments like sanctions, capital withdrawal, media narratives, diplomatic isolation. Contradictions are absorbed rather than resolved. The language adjusts. Control acquires a managerial accent.

I grew up in Brazil during the country’s democratic transition in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The dictatorship had formally ended. Elections were restored. A new constitution was being written.

But the most consequential decisions – on debt repayment, monetary policy, public spending – were treated as settled elsewhere. Negotiations with the IMF and international creditors placed strict limits on what the newly democratic state could do, even as political freedoms expanded.

Adults spoke in the language of realism. Certain reforms were described as impossible. Certain debts untouchable. Certain expectations irresponsible.

Democracy had returned. Its perimeter was carefully marked. The tanks were gone. The constraints remained. What changed was not the substance of power, but its method.

The issue is not whether constraint is technically possible, but which forms of constraint are considered legitimate.

Direct retaliation against the United States is widely understood to be unrealistic given financial infrastructure, currency dominance, and military reach. That recognition, however, often narrows the analytical field too quickly.

Constraint does not operate only through symmetry. It operates through friction: refusals to comply with unilateral measures; alternative payment and trade arrangements built incrementally; legal challenges that accumulate rather than resolve; reputation costs that alter the calculus of intervention.

Power weakens when its exercise becomes burdensome rather than unquestioned.

What is unfolding around Venezuela is therefore not an isolated dispute. It is a test of how far the gap between legal form and political enforcement can widen before restraint becomes optional in practice.

Latin America recognises the pattern because it has encountered it before: systems in which rules remained intact while their capacity to bind receded; democracies that functioned electorally while key decisions were made elsewhere; sovereignty that persisted formally while eroding operationally.

This is how orders decay:

through accommodation rather than rupture,

through selective enforcement rather than lawlessness,

through speech that continues while its force drains away.

Some regions have learned to recognise that moment.

Others are arriving there.